Insights from the Colonial Period: Bishop Rosendo Salvado and the Mission at New Norcia WA

Historic accounts of settlement and the early colonial period provide invaluabe insight into the lives of First Nations people, as well as the conditions and prejudice that they were forced to endure at the hands of the colonists. Even the altruistic approach of Bishop Salvado reflects the ingrained attitude of the Europeans in their need to ‘civilise’ the local population.

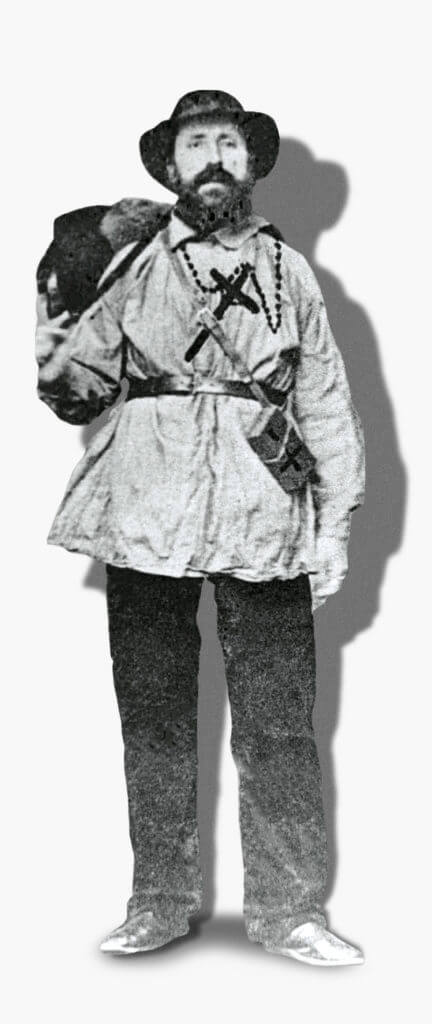

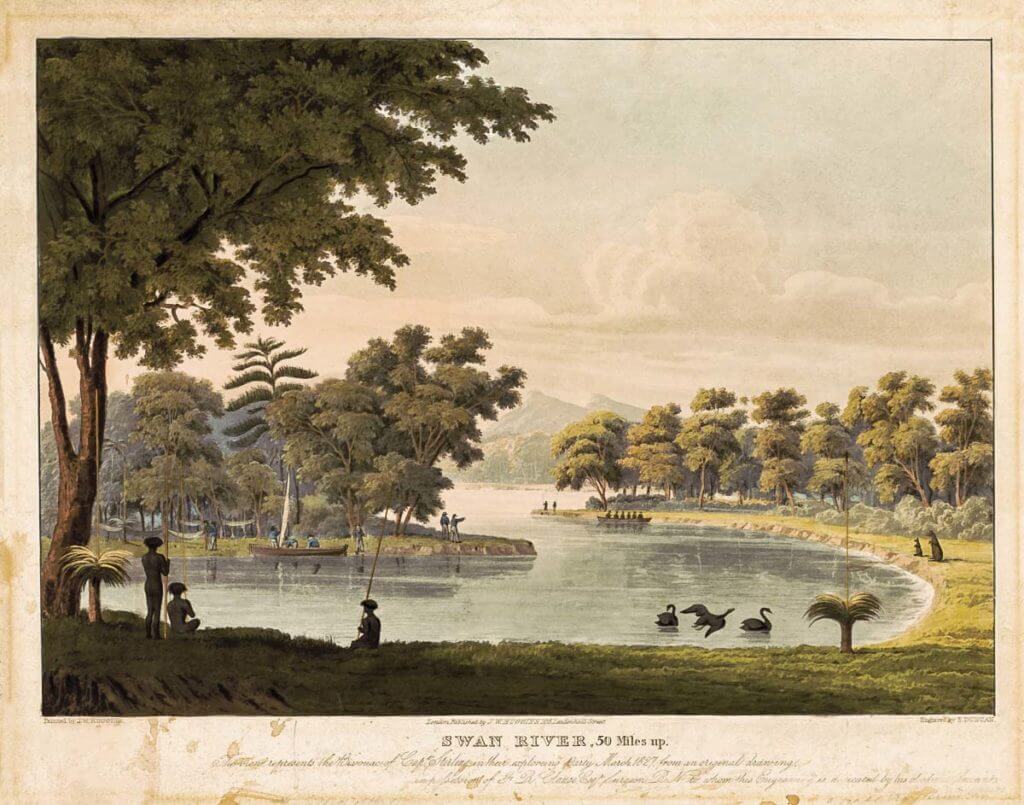

On 1 March 1846, a Benedictine mission to the local native Aboriginals was started about 8 km (5 mi) to the north, led by the two Spanish Benedictine monks, Rosendo Salvado and Joseph Serra. Within a year the mission was moved to where the town is today and on 1 March 1847 the foundation stone of the monastery was laid. The place was named New Norcia after Norcia in Italy, the birthplace of St Benedict.

“The establishment of the Aboriginal mission at New Norcia had a profound effect on the lives of the local Aboriginal people, the Yued people of the Noongar nation […]. We consider that Bishop Salvado was a friend of the Yued people […] [who] had a deep interest and respect for Aboriginal people in which he recorded the local Noongar language, culture and customs. Those records have provided important historical information about Noongar people, including being used to support the Noongar native title claim.”

Reference: Edited by Ramon Maiz and Tiffany Shellam. (2016). Rosendo Salvado and the Australian Aboriginal World. Consello, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Page 17.

“It seems impossible to some people to believe a native of Australia capable of working or doing any real material good for himself; and if they hear that a native has ploughed his field, has reaped his wheat, has sold it, has with those means bought bullocks and even mares, of which he is the rightful owner, they still will say, ” Impossible!” but against a fact no argument can stand. Surely, if the aborigines are left to themselves, they cannot but follow their forefathers’ traditions and customs, but if properly and timely trained, I, for one, do not see the impossibility of their being truly civilized,” Bishop Rosendo Salvado, 1864.

Reference: Habits and Customs of the Aboriginal Inhabitants, Compiled from Various Sources. (1871). Presented to the Legislative Council by His Excellency’s Command. Perth: By Authority: Richard Pether, Government Printer. Page 7.

His Lordship Rosendo Salvado, Bishop of Port Victoria, to The Hon. The Colonial Secretary, New Norcia, 19th February, 1864.

Indeed, it is very discouraging to hear that the Aborigines of Australia, as a race, are dying off and disappearing; but, why so? Because of the consumption, the bronchitis, the syphilis, the liver complaints, and several other diseases? If that is the true reason of it, then we may conclude, also, that all human races must die and disappear, for there is no country, that I am aware of, where there are not the same, nay, in several countries, even worse sickness and diseases than those that are said to be the cause of the Aborigines of Australia dying off and disappearing. I cannot help thinking that the true reason must be another. I do not wonder at the Aborigines dying, as the Europeans must die of one or other disease; but what seems rather strange is to see so few sick aborigines restored to health, whereas, in each similar case, so few Europeans would die (Page 1).

A native, I will suppose, is taken ill and brought to a hospital or private house; there the Doctor attends him daily and with care: nothing is wanting, nevertheless the native grows worse every day, and after a short time his life is despaired of. A European, in the same case, would have recovered his health by that time, but the unfortunate native is dying, there is no remedy for him. His disease has baffled the Doctor’s skill and care, and, as the last resource, the native is consigned to his relatives or friends, by whom he is brought to the woods and there by them taken care of in their own way. If an European, in the case of that native, had been sent to the open air in the bush, surely he would have died a few days, nay, a few hours, after; yet, that dying native a few weeks afterwards, and when everyone that knew him in his dying state believes him to be already dead and buried, there he is as healthy and as strong as ever, having perhaps travelled already fifty or more miles on foot. He had taken no medicine whatever since he had left the hospital or private house, yet he has perfectly recovered his health and his strength. To someone this case may seem a fancy or simply a supposition, but I assure him of its being a fact (Page 1).

What, then, ought we to conclude from such a fact, nay facts? If I was not considered too presumptuous in advancing an opinion, I should be tempted to say either the disease had not been well understood or the medicines administered Were not in harmony with the constitution of that native. The medicines administered to him would in time, and in all probability, have killed him; therefore, it seems clear enough those medicines were by no means healing remedies for him (Page 2).

Another case: a strong and healthy young native, who never in his life knew what strong liquors or European vices were, is admitted in a private house, mission, or establishment; for some time, he goes on well, gay and full of life; but few months, or perhaps after a couple of years, a fatal melancholy takes possession of him. Being asked what the matter with him is, he answers, “Nothing!” “Do you feel sick?” ” No, sir.” “Do you suffer any pain?” ” No, sir.” ” Why are you not so cheerful as before?” ” I do not know.” He takes his meals as regular as ever, he has no fever, yet he daily and almost at sight loses his flesh, strength, and health. What is the technical name of such a disease*? Perhaps consumption, perhaps liver complaint. Let it be so; but is there no remedy for such diseases? Are there no preventives of their causes? Yes, there are but, nevertheless, that native died shortly after (Page 2).

On various occasions I consulted several medical doctors on these and similar other points, but I regret to say all to no purpose. Nevertheless, one of them disclosed to me his utter ignorance of the diseases of the Aborigines, saying that he knew no more about them than a man in the moon. I asked him if he had ever made a post-mortem examination of their bodies, and he replied that he had done it repeatedly, but, after all, he knew no better or more than before! To this he added, that, as a rule, every time he had taken under his especial care any sick native, he succeeded only, he regretted to say, in killing him the sooner! (Page 2).

Almost everyone, in some degree conversant with the Aborigines of Australia, knows that a severe wound, which would oblige any European to keep his bed for a long time, would be considered by a native as nothing. A European perhaps would have died of it, but a native would be healed in an incredible short time. Medical men themselves are really astonished at how quick a native heals and recovers of his severe wounds, and on the other hand at in what a short time he dies of a disease. They wonder, and with reason, at both extreme cases, because the causes of both extreme cases are equally unknown to them (Page 2).

Miss Florence Nightingale’s question ” Can we civilize the Aborigines without killing them?” is not a simple question but a difficult problem, which heaven knows when will be solved. The natives of Australia seem to be yet a mystery to the medical world. Miss Nightingale, at page 14 of her pamphlet entitled ” Sanitary Statistics of Native Colonial Schools and Hospitals,” says that “The Hospital Returns ” throw little light on the causes of the disappearance of native races, unless these are to be found in the ” great prevalence of tubercular and chest diseases.” And again, at page 15, ” the discovery of the causes ” of this must be referred back to the Colonies.” It is also said in that pamphlet that ” anything which exhausts the constitution will engender these diseases,” viz., tubercular and chest diseases. But to this purpose I will relate another case (Page 2).

A young native has been ploughing here his own field for about three weeks, at the end of which time I ordered him to suspend his ploughing, for I had observed he was unwell. He stayed but unwillingly, seeing the other natives going ahead of him with their ploughing. After a few days continuing still to spit blood, he told me he would be all right in a few days if I would allow him to go hunting horses. I did not want any horses at that time, and much less him to do that hard work, which I considered very injurious to his case, nevertheless I consented to it as a trial. That native, after having been hunting for three or four days, ceased to spit blood, and immediately went again to his ploughing. I may not be right, but I always considered hunting horses as something that exhausts the constitution of any sound person, and the case will be the more aggravating if that person is spitting blood. But if I am right, how was it that that native was healed by doing it? (Page 2).

When I, in my difficulties, requested a medical man to direct me in the curing the diseases of the Aborigines, his direction has been ” Do your best in your own way, for if you follow my advice, and do as I should direct you to do, I am afraid the whole of your sick natives would die the sooner. The aborigines,” he added, ” cannot stand our recipes.” When a sick person is abandoned by the Doctor to the resources of his unlearned relatives or friends, we consider it as a desperate case: such seems to not to be the case of the aborigines (Page 2).

Reference: Information Respecting the Habits and Customs of the Aboriginal Inhabitants of WA, Compiled from Various Sources. (1871). Presented to the Legislative Council by His Excellency’s Command. Perth: By Authority: Richard Pether, Government Printer. Pages 2 – 4.

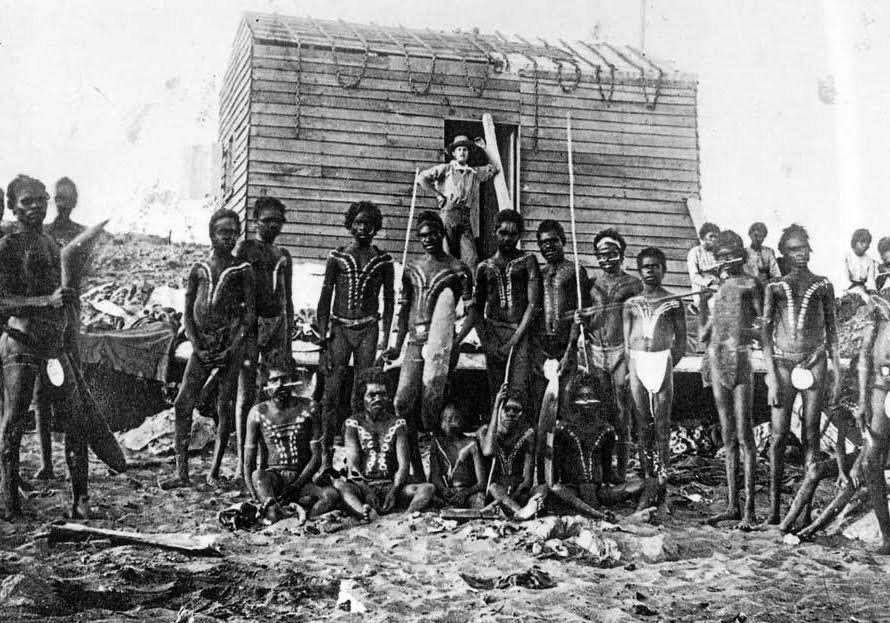

From the late 1860s to the 1880s successive epidemics of measles, influenza and whooping cough and a ‘fatal melancholy’ attributed by Salvado to Aborigines’ deep despair and grieving for family and homelands now lost to them cut a swath through the New Norcia mission population. New Norcia seemed doomed to follow the fate of missions elsewhere that began with high hopes ‘sustained during the first couple of years, followed by a period of gradual decline and ultimate collapse.’ We can only imagine the grief and trauma experienced by the families losing so many loved ones and the tragic legacy for the survivors (Page 127).

However, the real calamity now facing the mission was the threat to its economic survival as a viable pastoral and agricultural enterprise as the Victoria Plains district was opened up to establish a wheat export industry in the colony during the 1890s. This brought a dramatic shift in patterns of land tenure and usage in the region and mounting pressure for New Norcia’s extensive land holdings to be resumed by the government or sold off to be carved up into small farming blocks. By 1909 the mission held only 100,000 of its original holdings of 967,000 acres. Aboriginal farmers who had been encouraged to take up farming plots outside the mission also faced cancellation of the reserved land (Page 130).

Salvado was well into his eighties when he set out on his final trip to Europe in 1900. While there he appointed a successor who would negotiate new directions and strategies for the Benedictine mission endeavour in Western Australia. Salvado died while he was in Europe and in 1903 his remains were returned to the mission that he devoted his life’s work to establish. Under the new direction of Bishop Torres Salvado’s vision of a self-supporting community of monks and Christian Aboriginal families was progressively abandoned. The effort to convert Aboriginal souls shifted to establishing Kalumburu mission in the north Kimberley and at New Norcia boarding schools were built to cater for the superior education of white children with labour provided by children from the Aboriginal orphanages (Page 130).

Torres also directed the religious community to take up a more refined and secluded way of life. With less need for their labour, Aboriginal adults left to find work with local farmers and by 1911 only 10 men were regularly employed there. Despite Salvado’s assurances that the farms they had worked were theirs by right, they also found they had no recognised claims over the land they had tilled. With encouragement from the monks, some families left their children behind for schooling but access to the children was increasingly curtailed. Growing tensions finally erupted into conflict in 1908 and three of the mission’s former upstanding residents were sentenced to three months’ imprisonment. One of the men subsequently wrote that New Norcia was now ‘no home for the native at all. They keep a few hands here to carry bricks because they are cheap but I can assure you that if you are sick they have no time for such a native’ (Page 131).

Families now living in the surrounding Midlands district found they could only get menial farm work despite their schooling and skills in farming, trades and domestic duties. Accustomed to living a settled life in the mission cottages, they now had to live in tents in temporary camps, often in desperate conditions. Once protected by the mission community, they now experienced the virulent racism of settler farmers moving into the district and the full force of strict legislative controls enshrined in the 1905 Aborigines Act, which now directed the lives of Aborigines in the state and left them vulnerable to forced removal of their children, who could be sent to live in the New Norcia orphanages, which continued to operate until the 1970s (Page 131).

Reference: Edited by Ramon Maiz and Tiffany Shellam. (2016). Rosendo Salvado and the Australian Aboriginal World. Consello, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Page 127 – 131.