Alcohol and Harm in Australia 2019

At what age do people start drinking?

The NHMRC guidelines recommend that people under 18 do not drink alcohol and should delay their initiation as long as possible. In 2019, 2 in 3 (66%) 14–17-year-olds had never consumed a full standard drink.

The average (mean) age that 14–24-year-olds first consumed their full serve of alcohol in 2019 was 16.2 years. While this was not a significant change since 2016, it does continue an increasing trend seen since 2001, when the mean age of initiation was 14.7. Among females aged 14–24, the mean age at which they consumed their first drink increased since 2016, from 16.0 to 16.3.

How is risky drinking defined?

The NHMRC publishes the Australian Guidelines to Reduce Health Risks from Drinking Alcohol. The data for alcohol risks in this report are measured against the following guidelines:

- Guideline 1 (lifetime risk): For healthy men and women, drinking no more than 2 standard drinks on any day reduces the lifetime risk of harm from alcohol-related disease or injury.

- Guideline 2 (single occasion risk): For healthy men and women, drinking no more than 4 standard drinks on a single occasion reduces the risk of alcohol-related injury arising from that occasion. The NDSHS report focuses on the proportion of people who drank more than the single occasion guideline at least once a month on average.

- Guideline 3 (children and young people): For children and young people under 18 years of age, not drinking alcohol is the safest option.

- The number of people drinking at levels that put their health at risk has remained stable since 2016. In the case of lifetime risk, 17.2% of people in 2016, and 16.8% of people in 2019 drank more than 2 drinks per day on average, corresponding to 3.4 million people in 2016 and 3.5 million in 2019.

- The trend for single occasion risk was similar. The proportion of people drinking more than 4 drinks in 1 sitting at least monthly was about 1 in 4 in 2016 and 2019, representing around 5.1 million people in 2016 and 5.2 million in 2019.

- However, the results in 2019 continue a trend of declining risky drinking since the alcohol guidelines were introduced in 2009. From 2001 to 2010, people drinking at levels that exceeded the lifetime risk guidelines did not change substantially (21% both years). Since 2010, the proportion has declined to 16.8%.

- Single occasion risk (at least monthly) follows a similar trend, dropping by only 1 percentage point between 2001 and 2010 (30–29%), but declining to 25% by 2019.

- However, these declines do not mean that fewer people are at risk of injury or illness, due to the population increasing over the same time frame. In 2001, approximately 3.3 million Australians had consumed alcohol at levels that exceeded the lifetime risk guideline, while in 2019, 3.5 million people had done so. The number of people exceeding the single occasion risk at least once a month has increased substantially since 2001, from 4.6 million to 5.2 million. In the same period, the number of people abstaining from alcohol has almost doubled, from 2.6 million to 5.0 million.

Lifetime risky drinking remains common among older Australians

Despite people aged 70 and over being the most likely to drink alcohol daily, people in their 40s and 50s were the most likely to exceed the lifetime risk, both at 21%. The only statistically significant change since 2016 was an increase among females aged 70 and over, although this remained the adult age group least likely to exceed the lifetime risky drinking guideline (4.0% in 2016, increasing to 5.9% in 2019).

Single occasion risky drinking becoming more common among older people

Consistent with 2016, single occasion risk was most likely to be exceeded at least monthly by people aged 18–24 (41%, compared with 42% in 2016) and 25–29 (36%, the same as 2016). People in their 30s were less likely to have done so in 2019 (28%) than in 2016 (31%).

However, 27% of people in their 50s exceeded the single occasion guideline at least monthly, an increase from 25% in 2016. The proportion of people aged 70 and over drinking this amount also increased, from 7.2% to 8.8%.

What proportion of people have consumed 11 or more drinks on a single occasion?

In addition to reporting against the NHMRC guidelines, it is important to examine other drinking patterns among people who exceed the guidelines, including those people who drink well in excess of the guidelines—those consuming 11 or more drinks on a single occasion.

In 2019, there was a decline among the adult population drinking 11 or more drinks in a single session at least once a month, from 7.4% in 2016 to 6.7% in 2019. There was also a slight but non-significant decline among people aged 14 and over (from 7.1% in 2016 to 6.5% in 2019).

People drinking at these levels at least yearly did not change over the latest 3-year period but has declined since 2010 from 17.4% to 15.1% in 2019.

As with single occasion risk, young adults (aged 18–24) continued to be the most likely age group to drink 11 or more drinks on a single occasion in 2019, with 30% having done so in the past year, and 14.6% doing so at least monthly.

How does drinking vary across Primary Health Network areas?

Primary Health Networks (PHNs) are organisations that connect health services over local geographic areas according to boundaries defined by the Department of Health. There are 31 PHNs in Australia.

Across PHNs there was wide variation in the use of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs in 2019.

South Western Sydney (8.5% and 14.3%) and Western Sydney (7.6% and 15.4%) had the lowest proportions of both lifetime risk and single occasion risk (at least monthly) drinkers; Murrumbidgee had the highest lifetime risky drinkers (25%); and the Northern Territory had the highest proportion of single occasion risky drinkers (35%). After adjusting for differences in age, North Coast and Country Western Australia had the highest proportion of lifetime risky drinkers (24%) and Western Victoria had the highest proportion of single occasion risky drinkers (38%). In a number of PHNs, over 10% of people were estimated to have a high-risk ASSIST score and may require referral to specialist treatment services for assessment of their alcohol use:

Country WA (12.5%)

Gippsland (10.7%)

South-eastern NSW (10.3%)

Brisbane North (10.1%).

1 in 10 people who drink may be experiencing alcohol dependence

The NHMRC alcohol guidelines were developed to provide an indication of how people’s alcohol consumption may have an impact on their health, either through chronic health conditions or by increasing their risk of injury while affected by alcohol. However, it is also important to consider how many people may be dependent on alcohol. Alcohol dependence is a different form of harm that is likely to require specialised alcohol treatment services, rather than presentation to a doctor or an emergency room to treat alcohol-related health issues.

The ASSIST: A Measure of Harmful Use

The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) was developed by the World Health Organization to identify people whose substance use may be causing them harm. The ASSIST screens for harmful use of alcohol and tobacco, as well as illicit drugs and pharmaceuticals.

ASSIST scores are categorised as ‘low risk’, ‘moderate risk’ or ‘high risk’. High risk scores are likely to indicate a substance dependence issue, while moderate risk scores indicate substance use that may be hazardous or harmful to the person’s health.

The ASSIST-Lite is an abridged version of the ASSIST, consisting of 3 to 4 questions for each substance. It was incorporated into the NDSHS in 2019 to estimate how many people who use substances show signs of substance dependence, or a pattern of use that may be hazardous to their health. Results also have implications for alcohol and other drug treatment services in Australia: people who receive a high-risk score are likely to require specialist assessment and treatment for their substance use, while people who receive a moderate risk score are likely to benefit from a brief intervention or education of some kind.

Of everyone who had an alcoholic drink in the previous 12 months, 9.9% were likely to meet the criteria for alcohol dependence. Males (13.5%) were more likely than females (6.3%) to receive this score. The ASSIST-Lite scores indicated that a further 29% of this population were using alcohol to a hazardous or harmful extent, and again males (36%) were much more likely to meet this threshold than females (22%).

Among the total Australian population aged 14 and over, this equates to 7.5% who may be experiencing some form of alcohol dependence and would benefit from specialist treatment, and a further 22% who are likely to be using alcohol in a harmful way.

Of the people identified as being at high risk (likely to have some extent of alcohol dependence):

- 74% had never participated in any form of tobacco, alcohol or other drug treatment program (such as a telephone helpline, counselling, or medications to help with their drinking), and only 12.5% had done so in the previous 12 months

- 27% had been diagnosed or treated for a mental illness in the previous 12 months, much higher than the 16.7% proportion of the general population.

- Of the people identified as being at moderate risk (likely to be negatively affected by their alcohol use):

- 89% had never participated in any form of tobacco, alcohol or other drug treatment program, and only 3.9% had done so in the previous 12 months

- 17.8% had been diagnosed or treated for a mental illness in the previous 12 months

How many people were harmed by other people’s alcohol use?

A person’s alcohol consumption can harm others, not just themselves. The NDSHS contains several questions about whether the respondent has experienced harm from another person who was under the influence of alcohol. Specifically, people were asked whether they were verbally or physically abused or put in fear by another person who was under the influence of alcohol.

More than 1 in 5 people (21%) had been verbally or physically abused or put in fear by someone under the influence of alcohol in the previous 12 months, corresponding to 4.5 million Australians—little change from 2016.

The proportion of males who had experienced physical abuse from someone under the influence of alcohol in the previous 12 months decreased since 2016, from 6.8% to 5.6% in 2019, representing a decline from 700,000 to 600,000 males.

The proportion of females who experienced physical abuse also decreased from 5.0% to 4.0% (or 500,000 to 400,000). In the same time frame, verbal abuse decreased, from 17.2% to 15.9%, but the number remained unchanged at 1.7 million.

Of all incidents of physical abuse, 10.6% were serious enough to require admission to hospital.

Some people are more likely to experience harms than others

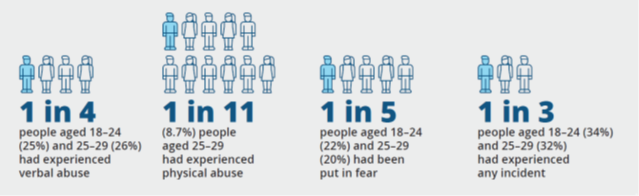

Younger adults were disproportionately abused and put in fear by people under the influence of alcohol:

The proportion of incidents is also much higher among people who exceed the single occasion drinking guideline.

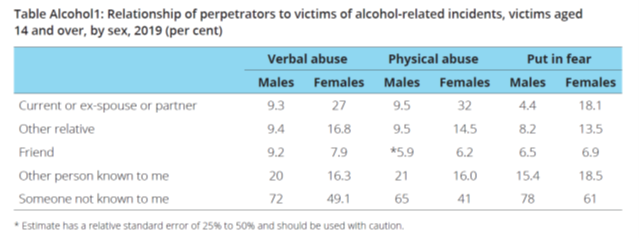

Who are the perpetrators of alcohol-related harms?

Despite similar proportions of males and females having experienced harms in the previous 12 months, the people responsible for those harms are different. Females were more likely than males to report their abuser being their current or former spouse or partner, while males were more likely to report their abuser being a stranger. This indicates that the types of abuse being experienced by females and males are likely to take different forms and may occur in different places, so different strategies are required to reduce the number of people experiencing abuse or fear from people who are under the influence of alcohol.

Reference: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2019. Drug Statistics series no. 32. PHE 270. Canberra AIHW. Pages 22 – 25.