Social and Emotional Wellbeing: SEWB

Health and wellbeing are complex concepts and there is no clear consensus across or within cultures as to how these constructs should be defined. Policy makers, researchers and practitioners working to improve the social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) and mental health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia must grapple with the task of defining these health concepts in terms that are relevant and consistent with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander understandings and experiences. The linguistic and cultural diversity that exists within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures needs to be acknowledged from the outset, as there are significant differences in the way SEWB, mental health and mental health disorders are understood within different Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across Australia (Page 55).

The uptake of the term ‘SEWB’ (social and emotional wellbeing) to reflect holistic Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander concepts of health can be traced to the early efforts of these organisations to define health from an Aboriginal perspective. In 1979, the National Aboriginal and Islander Health Organisation (now the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation) adopted the following definition of health:

“Aboriginal health does not mean the physical wellbeing of an individual, but refers to the social, emotional, and cultural wellbeing of the whole community. For Aboriginal people this is seen in terms of the whole-life-view. Health care services should strive to achieve the state where every individual is able to achieve their full potential as human beings, and must bring about the total wellbeing of their communities.” (Page 56).

This definition was used in the first National Aboriginal Health Strategy (NAHS). In the section devoted to mental health, the NAHS Working Party held a strong line, arguing that ‘mental health services are designed and controlled by the dominant society for the dominant society’ and that the health system had failed ‘to recognise or adapt programs to Aboriginal beliefs or law, causing a huge gap between service provider and user’. One of the strategy’s key recommendations was for a health framework to be developed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples that recognised the importance of culture and history, and which defined health and illness from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspective (Page 56).

The term SEWB signifies an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander concept of wellbeing that differs in important ways to Western concepts of mental health. We suggest that, within the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander SEWB and mental health landscape, SEWB signifies a relatively distinct set of wellbeing domains and principles, and an increasingly documented set of culturally informed practices that differ in important ways with how the term is understood and used within Western health discourse (Page 57).

The Relationship Between SEWB and Mental Health

Mental health and wellbeing is an important component of SEWB, but needs to be viewed as only one component of health that is inextricably linked to the social, emotional, physical, cultural and spiritual dimensions of wellbeing. The 2004 SEWB framework describes an interactive relationship between SEWB and mental health, where the two may influence each other and where a person can experience relatively good SEWB and yet still experience mental health problems, or vice-versa. SEWB problems include a wide range of issues, such as: ‘grief, loss, trauma, abuse, violence, substance misuse, physical health problems, child development problems, gender identity issues, child removals, incarceration, cultural dislocation, racism and social disadvantage … while mental health problems may include crisis reactions, anxiety, states, depression, post-traumatic stress, self-harm, and psychosis’. Many of the issues identified as SEWB problems, such as abuse, violence, racism and social disadvantage are also well-established risk factors for various mental health disorders, suggesting that in some cases mental health disorders are likely to be symptomatic of greater SEWB disturbance. The framework also emphasises that cultural and spiritual factors can have a significant impact on the ways mental health problems develop, by influencing the presentation of symptoms and psychological distress, the meaning attributed to this distress, and the appropriateness of different therapeutic approaches and expected outcomes (Page 63).

The 2004 SEWB framework sets out nine guiding principles that were developed during the Ways Forward national consultancy. These guiding principles shape the SEWB concept and describe several core Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural values (Page 57).

Nine Guiding Principles That Underpin SEWB

1. Health as holistic

2. The right to self-determination

3. The need for cultural understanding

4. The impact of history in trauma and loss

5. Recognition of human rights

6. The impact of racism and stigma

7. Recognition of the centrality of kinship

8. Recognition of cultural diversity

9. Recognition of Aboriginal strengths (Page 57).

Social and Emotional Wellbeing from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders’ Perspective

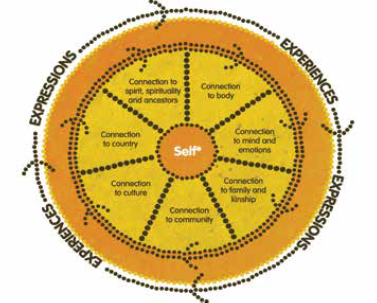

*This conception of self is grounded within a collectivist perspective that views the self as inseparable from, and embedded within, family and community. © Gee, Dudgeon, Schultz, Hart and Kelly, 2013, Artist: Tristan Schultz, RelativeCreative (Page 57).

We note the somewhat artificial separation of these areas of SEWB and recognise that the cultural diversity that exists amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples means that no single grouping is necessarily applicable or relevant for every individual, family or community (Page 57).

The diagram shows that the SEWB of individuals, families and communities are shaped by connections to body, mind and emotions, family and kinship, community, culture, land and spirituality (the important role of broader level determinants is also addressed below). The term ‘connection’ refers to the diverse ways in which people experience and express these various domains of SEWB throughout their lives. People may experience healthy connections and a sense of resilience in some domains, while experiencing difficulty and/or the need for healing in others. In addition, the nature of these connections will vary across the lifespan according to the different needs of childhood, youth, adulthood and old age (Page 58).

If these connections are disrupted, and for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and families some of these connections have been significantly disrupted in multiple ways as a result of past government policies associated with colonisation, then they are likely to experience poorer SEWB. Conversely, restoring or strengthening connections to these domains will be associated with increased SEWB (Page 58).

Connection to Body, Mind and Emotions

The wellbeing domains we have termed connection to body, and mind and emotions, refer to those aspects of health and wellbeing that are rooted in bodily, individual or intrapersonal experience (Page 58).

Connection to Body

Connection to body is about physical wellbeing and includes all of the normal biological markers and indices that reflect the physical health of a person (i.e. age, weight, nutrition, illness and disability, mortality) (Page 58).

Connection to Mind and Emotions

Connection to mind and emotions refers not only to an individual’s experience of mental wellbeing (or mental ill-health) but also the whole spectrum of basic cognitive, emotional and psychological human experience, including fundamental human needs such as: the experience of safety and security, a sense of belonging, control or mastery, self-esteem, meaning making, values and motivation, and the need for secure relationships. The 2008 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey found that most adults reported feeling happy, calm and peaceful, and full of life, all or most of the time. However, nearly one-third of adults reported experiencing high to very high levels of psychological distress (more than twice the rate for other Australians) and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are 31 times—and men 25 times— more likely than other Australians to be admitted to hospital as a result of family violence-related assaults.26 Given these alarming statistics, we stress the primacy of personal safety and freedom from abuse as a most fundamental human right and determinant of SEWB (Page 58).

Connection to Family, Kinships and Community

The SEWB domains of connection to family and kinship, and community, refer to aspects of wellbeing that are rooted in interpersonal interaction (Page 59).

Family and Kinship

Family and kinship systems have always been central to the functioning of traditional and contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies. These systems are complex and diverse and serve to maintain interconnectedness through cultural ties and reciprocal relationships. Milroy states:

These systems locate individuals in the community and neighbouring clans within relationships of caring, sharing, obligation and reciprocity. Essentially, the kinship system provided a very secure attachment system that established caring relationships, so that everyone grew up with multiple carers and attachment figures and, in turn, provided care for others (Page 59).

She also notes that in contemporary society, kinship and cultural obligations can place significant burdens on members of the family. Grandmothers, for example, may not have the adequate levels of support and resources necessary to care for large numbers of family. It is important that practitioners develop an understanding of the different language and family groups of the communities they work in. In traditional regions, this usually includes moiety or skin group systems that can entail complex avoidance relationships that determine the nature and extent of interaction between different family and kin members (Page 60).

Community

The concept of community has been described as fundamental to identity and concepts of self within Aboriginal cultures, a collective space where building a sense of identity and participating in family and kinship networks occurs, and where personal connections and sociocultural norms are maintained. The establishment of ACCHOs has been found to play an important role in strengthening cultural identity and fostering a sense of ownership, cultural pride and belonging for some communities (Page 60).

Connection to Spirituality, Land and Culture

Spirituality

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ cultural worldviews include beliefs and experiences that are grounded in a connection to spirituality. Within traditional contexts, the essence of spirituality has been most popularly translated and depicted as ‘The Dreaming’ or ‘The Dreamtime’, which has become an iconic referent for Aboriginal metaphysical world views, though Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nations and language groups have different terms, practices and epistemologies that reflect these world views (Page 60).

These understandings of spirituality broadly refer to a cultural group’s traditional systems of knowledge left by the ancestral beings that typically include all the stories, rituals, ceremonies, and cultural praxis that connect person, land and place. In ceremony, the critical transitions from childhood to adulthood, and other life stages, are marked through specific rites of passage. It is through ceremony and everyday cultural praxis that children, women and men of the community learn about their culture’s systems of moral and ethical practices that guide behaviour, and determine their personal, familial and cultural rights, obligations, and responsibilities (Page 60).

Perhaps here, in the connection to spirit and spiritualty, the consequences of colonisation for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are most keenly felt, because for many this has involved a permanent severance of the links to their traditional customs, leaving a cultural void and an unfulfilled longing and need for recreating and redefining the spiritual. It is not surprising then, that Poroch and colleagues in their review of spirituality and Aboriginal SEWB have found that spirituality is an evolving expression of Indigeneity that in contemporary Aboriginal cultures is experienced in a multitude of ways. They note that spirituality for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples today has been transformed by engagement with other cultures, and is now experienced in multiple contexts, including in combination with and alongside other religions; in contemporary Aboriginal healing practice settings; and as an ethos related to a holistic philosophy of care that underpins community-controlled health centres and other types of Aboriginal organisations (Page 60).

Land or ‘Country’

For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, spirituality is closely tied to their connection to land or ‘country’. Country or land has been described as an area to which people have a traditional or spiritual association, and the sense of connection as a deep experience, belief or feeling of belonging to country (Page 60).

Connection to country and land extends beyond traditional cultural contexts, however, and the SEWB literature documents the importance of country across the whole spectrum of diverse Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural groups around Australia (Page 61).

Culture

Connection to culture, as we use the term here, refers to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ capacity and opportunity to sustain and (re) create a healthy, strong relationship to their Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander heritage. This includes all of the associated systems of knowledge, law and practices that comprise this heritage. Culture is, of course, a complex concept to try and define or articulate. We ascribe to Hovane and colleagues (2013) articulation of Aboriginal culture as constituting a body of collectively shared values, principals, practices and customs and traditions—Chapter 30 (Hovane, Dalton and Smith). Within this context, maintaining or restoring SEWB is about supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to maintain a secure sense of cultural identity and cultural values, and to participate in cultural practices that allow them to exercise their cultural rights and responsibilities (Page 61).

This can be deeply rooted in areas of wellbeing such as connection to spirituality and land, but also might not be due to the large variation and increasing complexity of Aboriginal identity. We suggest that important roles for practitioners include, for example, supporting people to develop and strengthen a sense of continuity and security in their Indigenous identity, supporting people to re-affirm and strengthen their cultural values, and assisting them to develop effective strategies to respond to racial discrimination, which has been shown to be associated with depression, anxiety, and other mental health difficulties (Page 61).

The wellbeing domains of spirituality, land and culture can be sensitive and complex areas to work with. For some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and communities, the extent of cultural loss associated with colonisation has been profound. Many members of the Stolen Generations and their descendants continue to experience a deep grief and a longing to reconnect with their cultural heritage and ancestry. With appropriate cultural supervision, and in the right circumstances, it is important for practitioners to be able to provide clients with an opportunity to discuss whether issues such as cultural loss, identity and belonging are in any way linked to their current difficulties, and whether personal work in this area is important for their healing process. Practitioners need to make sure they have a sound knowledge of the appropriate cultural services available in the community (Page 61).

Reference: Pat Dudgeon, Helen Milroy and Roz Walker. (2014) . Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice. Commonwealth of Australia 2014. Pages 55 – 63.