The Burden of Disease

The top causes of disease burden among Australians are dominated by mental health and alcohol or other drug use (AOD) disorders. Of significant concern is the common co-occurrence (i.e. comorbidity) of mental health and AOD disorders. It is estimated that almost one in five Australians with a mental health disorder also have a co-occurring AOD disorder. Conversely, between 47-100 per cent of people in AOD treatment in Australia have co-occurring mental health disorders. This common comorbidity remains a major cause of disability, poor quality of life, early mortality and poses a significant challenge for the Australian health system.

Research demonstrates that integration of mental health and AOD treatment is key to enhancing outcomes for individuals with comorbidity and preventing them from falling through the gaps. However, despite the growing evidence and governmental responses regarding integrated treatment, individuals experiencing comorbidity continue to receive disparate care targeting either their mental health or AOD disorder. Individuals can find themselves on a ‘comorbidity roundabout’, moving from one service to another and navigating a complex range of factors in attempt to access treatment.

In response to the increasing need to better address mental health and AOD comorbidity, standardised toolkits were developed in the United States to improve comorbidity competency among treatment services: The Dual Diagnosis Capability in Mental Health Treatment (DDCMHT) and Dual Diagnosis Capability in Addiction Treatment (DDCAT) toolkits are designed for mental health treatment services and AOD treatment services, respectively, to assess capability of addressing comorbidity across seven dimensions: program structure, program milieu, assessment, treatment, continuity of care, staffing, and training.

Studies in the US and Australia have demonstrated effective implementation of these toolkits and associated improvements in comorbidity competency ratings (for example, the Western Australian Network of Alcohol and other Drug Agencies 2011). However, no study to date had examined the perspectives of people with lived experience of comorbidity in relation to the utility of these resources. As the perspective of these individuals is critical to informing the implementation of these toolkits in Australia and for enhancing comorbidity competency of Australian treatment services, this mixed methods study sought to examine the perspectives of Australian adults with lived experience of mental health and AOD comorbidity.

All participants reported experiencing mental health problems and AOD-related problems at some point in their lifetime. Their first such experience occurred, on average, at ages 18 (SD=8.99) and 27 (SD = 9.67), respectively. Most participants (89.5 per cent) had been diagnosed with a mental health disorder by a professional, of which the most common was depression (94 per cent), followed by post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (65 per cent), generalised anxiety disorder (41 per cent), social anxiety (29 per cent), eating disorder (24 per cent), bipolar disorder (24 per cent), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (12 per cent), panic disorder (6 per cent) and borderline personality disorder (6 per cent). More than half (68 per cent) had been diagnosed with an AOD disorder and, among those diagnosed, alcohol was the main drug of concern (53.8 per cent), followed by amphetamines (38.4 per cent), other opiates (30.7 per cent), heroin (23 per cent), benzodiazepines (23 per cent) and cannabis (15.3 per cent).

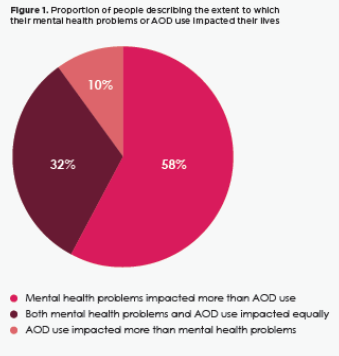

As depicted in Figure 1, over half the sample reported that their mental health problems had impacted their lives to a greater extent than their AOD use. Only 10 per cent reported that their AOD use impacted their lives to a greater extent than their mental health problems.

(Page 39).

All participants described experiencing stigma and discrimination because of their mental health and AOD use.The majority had encountered situations where they heard others say offensive things about people with AOD use problems (95 per cent) and about people with mental health problems (90 per cent). Almost two-thirds (63.1 per cent) felt they were treated as less competent by others upon revealing their mental health issues and almost all (95 per cent) had avoided stating their AOD issues on written applications (e.g., for jobs, licenses, housing etc.) for fear it would be used against them. Others (47.4 per cent) perceived they had been turned down for a job for which they were qualified when their health issues were revealed.

Almost all participants (95 per cent) had received some form of treatment for their mental health in their lifetime (i.e., 89 per cent outpatient counselling, 56 per cent inpatient treatment, 44 per cent peer recovery support) and just over half the sample (58 per cent), had received treatment for their AOD use (91 per cent detoxification, 82 per cent peer support, 64 per cent outpatient counselling, 55 per cent maintenance therapies, 18 per cent residential rehabilitation).The ages at which these individuals first sought treatment for their mental health problems and AOD use were 25 years (SD=6.3) and 29 years (SD=7.69), respectively.

Only 16 per cent of those who had received mental health treatment said they were made aware and could access services for their AOD use. On the other hand, 60 per cent of those who had accessed AOD treatment were made aware of services to support their mental health problems. Two-thirds (64 per cent) of the sample reported that they would prefer to work on their mental health and AOD use in an integrated way, with 27 per cent preferring to work on the AOD use prior to their mental health problems and 9 per cent wanting to work on their mental health problems first. Participants explained that their preference for integrated treatment was because they viewed their mental health and AOD problems as interlinked.

Close to three-quarters (73 per cent) of participants would prefer to have the same therapist working on both issues.Having different therapists for these issues was seen as a barrier to establishing a connection and developing rapport with a treatment provider. In relation to previous experiences of mental health treatment, between 42-58 per cent of participants indicated that the dimensions had not been adequately addressed to respond to their comorbidity.Some remarked that ‘assessment is not often done thoroughly enough’ and they’ve ‘never been asked about comorbid health issues.’ A slightly smaller proportion (between 32-58 per cent) reported that the toolkit dimensions were not adequately addressed in their previous AOD treatment experiences. Participant reasons included that there are ‘not enough workers and funding’, it is a ‘difficult system to navigate’ and there is ‘no acknowledgment of dual diagnosis.’

Several participants discussed other important factors they thought were not covered by the toolkits. These included employing workers with lived experience in treatment facilities and the importance of building a rapport with the treatment provider. Additionally, trauma informed care and support services for families and carers of individuals with co-occurring disorders were highlighted as important considerations.

Reference: Barrett, E., et al. (2019). Lived experiences of Australians with mental health and AOD comorbidity and their perspectives on integrated treatment: Newparadigm Summer 2018 – 2019. NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence in Mental Health and Substance Use, National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC), University of New South Wales, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Newcastle, Australia. Pages 38 – 42.